Esta tercera y última parte de la extensa crónica dedicada a Ramón Novarro se publicó en Motion Picture Magazine de junio de 1927 (Vol. XXXIII, No. 5, pp. 66-67 & 88 & 93-95 & 118). Las fotografías también provienen del mismo artículo.

On the Road with Ramón III

by Herbert Howe

Ideals do count. According to this last chapter in the Novarro biography, it is because of their ideals that the greatest stars not only have won their high places but held them

The Road of the Future

I was lying boastfully on the beach in swimming trunks. Boastfully, because it is something of a feat to lie on a beach in the winter in California, no matter what the advertisements say.

A pelican was swimming in the air overhead. I was wishing to be a pelican in the next life. I love travel, and the pelican takes it so easy, lying down as it were. One beat of his wings carries him a greater distance than a man can negotiate with five hundred movements of his legs. And the pelican takes his food where he finds it. He can eat anything. One almost swallowed a whale the other day. I was worried as I saw the one overhead make a swoop toward my brother’s cabin where the community Ford was standing. I wonder how a Ford would digest.

“Mr. Howe, telephone!” Mein friend, the German innkeeper, who serves me sauces and philosophy with my stakes, was calling me from the embankment. I draped a towel over as much of me as possible, wondering what pest had gotten on my trail, for my hermitage among the rocks is not easy of access even by telephone.

“Long distance. Los Angeles,” said the Inn Philosopher. “Mr. Novarro calling you.”

“Hello, Ramón.”

“Hello, Herb… Say, Herb, would you like to go to Cuba?”

“No.”

“You wouldn’t?”

“No. The swimming is good here, and the islands across are full of bootleggers, so why Cuba?”

“Oh, I see. “Well, how about Quebec?”

“Quebec? That’s where it snows in the winter… I’d like Quebec.”

“All right, then we’ll leave Sunday.”

“Fine. I’ll be in Saturday and give you a ring.”

“Fine.”

“Fine.”

“I’m going to Quebec,” I said to the innkeeper, as he prepared me a steak with one of his secret sauces which put you in a Lucullian mood.

“Quebec’s a nice place,” he said. “All French.”

Then I recalled a little French girl from Quebec whom I had met on my first trip to Europe after the war. She was on her honeymoon. Her husband was a good scout. We had cocktails together every evening before dinner. She always took just two in a precise, charming little way. “Ze first,” she said, “ees for appetite, ze second to drive eet home.” She drove home much faster than her husband and I.

Quebec… French girls… snow.

You get to longing for snow in California, especially if you happen to have been born in a Dakota igloo during a blizzard. Remember the blizzard of 1860?

As for French girls… remember the war of 1918?

At Home on the Wing

When the train porter had stacked our bags around us in the train compartment, Ramón relapsed with a sigh of contentment. “Well, home again.” he said.

“It’s a nice old covered wagon,” I said looking around.

Just then a reporter broke in. He wanted Mr. Novarro’s opinion of the train. It was the first flyer in a new service out of Los Angeles. Ramón spoke enthusiastically of it. He hadn’t been outside the compartment, but he knew he liked trains in general. Most people do who live in Hollywood.

“You look more at home in a train or a boat than in your house in Beverly,” he said to me.

“You don’t look out of place yourself.” I rejoined.

When you consider that the Road of Ramón has taken us half a million miles in the past three years, you can understand why we, like the pelicans, are more at home on the wing.

When Ramón signed a contract with Marcus Loew more than three years ago, he specified a vacation of two months every year. Every actor of Hollywood ought to get away for that space of time each year, if only to get a perspective on his little self.

“When I’ve finished this contract in two years, I’m going to Europe and stay as long as I like,” mused Ramón. “I’ll do Spain and the Riviera — and Italy again, of course. And I’m anxious to go to Berlin. I want to study music there, and I’d like to do my first concerts in Europe. Over here I’m afraid they’d come to see a movie star — out of curiosity. The Germans are not moved by publicity where music is concerned. You are judged on your merits.”

We arrived in Quebec at night. Lights were beaming from the little shop windows as we drove thru the twisting streets. The place had for us a charm as instantaneous as that of Miss Garbo upon the American public. We decided unanimously to remain a week instead of three days.

Usually Ramón does not register his name at a hotel But he did at Chateau Frontenac. The clerk had said the rooms would be ten dollars a day. When he read the name on the register, he looked up with a smile and extended his hand. “We are glad to have you, Mr. Novarro.” he said. «The rooms will be eight dollar a day.”

“So the name of Novarro must be worth two dollars,” laughed Ramón.

Quebec

Quebec is one of the most charming cities of the Road. Ramón considers it with Annapolis among the typical places of America. Annapolis, where he made “The Midshipman,” is one of his favorite spots in the world. “This,” he declared, “is America — the United States.” Quiet and culture and courtesy were everywhere. The officers of the Academy entertained Ramón in their homes, but there was none of the fanfare or insistence which so often accompanies the hospitality accorded a picture star.

The same spirit permeated old Quebec, the genuine aristocracy of the New World. The theater managers called but did not ask for personal appearances; however, Ramón made one in behalf of a church charity. The editor of Le Soleil, the French newspaper, offered to show us the town and each day published bulletins on Ramón’s activities.

The premier extended an invitation to Novarro to visit the parliament buildings, and afterward the minister of agriculture took us for lunch at the old club. There were no cameras grinding when the premier received Ramón. It was not a publicity stunt, but a gesture of real hospitality. “We regard you,” he said, “as an aristocrat of pictures. Ben-Hur is a true nobleman.”

French Girls and Autographs

Instead of requests for pictures, Ramón was besieged for his autograph. People located his room in the hotel and came up unannounced with autograph books in hand. He had to change his room three times in order to get sleep.

“But they are so charming you can’t turn them away,” he said.

I understood when on a few occasions I went to the door and found gasping little French girls with their books open and their fountain pens ready.

“Mr. Novarro is sleeping,” I told one of them. “I will take the book and have him autograph it. You may call for it later.”

She hesitated a moment and then said shyly, “Pleas’ but I would wish to see him also.” I assured her that when she returned she would see the hand that wrote the magic name.

Music Hath Charms

Ramón spent hours in a music store getting old Canadian and French songs. Le Soleil made note of the fact in its columns. The next day several people called offering him music. “And imagine, I had the bad taste to ask the price when the first one called,” said Ramon. “I thought of course he was a salesman. What gracious people these Quebec-ers are!”

There was no piano in our rooms, so at midnight, when everyone had left the hotel, we would go down to the ballroom. Mounting to the stage, Ramón would sit down at the grand piano in the darkness and play for the benefit of me, the janitor and the scrub ladies, who sat trancelike over their mop pails in the outer lighted room.

Cameras did not click until Ramón waved adieu to Quebec from the train platform. Back in the compartment on the way to New York, he wrote telegrams of appreciation to all Quebec.

Prophets Predict

Everyone is interested in a woman’s past and a man’s future.

Dareos the Seer predicts that Ramón will quit the screen to become a priest.

That would be a new drama for Hollywood, tho old in the world of literature where romantic characters often turn from the flesh-pots to a life of the spirit. It is indeed the story of the greatest characters that have, shadowed this world screen — philosophers, artists and men who later were made saints and gods.

A still more remarkable story would be for Novarro to become a priest and remain on the screen. I hasten to add that I speak figuratively, not heretically.

The Gospel of Art

It is true that Ramón is religious. But I believe the expression of his ideals will be thru pictures and music rather than by sermons. Music is the ritual of his devotion. Music affects our feelings directly and not thru the medium of ideas. Schopenhauer points out: it speaks to something subtler than the intellect. And so with masterpieces of human likeness, he says, “That peace which is above all reason, that perfect calm of the spirit, that deep rest, that inviolable confidence and serenity… as Raphael and Correggio have represented it, is an entire and certain gospel.”

Novarro is an actor, a musician, a mystic and something of a poet, but overall he is a spiritual symbol to the imagination. “The friend of man,” says Harry Carr of him. “The friend of that clean, fine thing inside your soul that never quite surrenders even in the worst of us.”

The screen offers an opportunity — unrealized as yet — for a man to be the Artist of Himself, as Raphael and Correggio were the painters of others.

Peter the Hermit

I stopped recently at a photographer’s shop on Hollywood Boulevard to get some prints of Novarro’s photographs for an Eastern publication. While I was waiting, the door flew open and in blazed Peter the Hermit.

“Soul!” shouted Peter, pointing to a portrait of Ramón in the window. Peter himself was the picture of a prophet standing there, barefooted, staff in hand, his rock-hewn face in a halo of silver locks. I thought of that other Peter as painted by Guido Reni; here, too, was one of life’s masterpieces.

“Soul!” he repeated fervently, then turning to Mandeville, the photographer, “God bless ye, my man, ye have shown the lad’s soul. I have known him since the day he came a lad to Rex Ingram, and I’ve been waitin’ and waitin’ for a great artist to bring it out. And there it is. I tell ye it is a fine face. The whole world will be the better for a-gazin’ on it. God bless ye, too, dear sir!”

With a wave of his hand, he pattered off, followed by his shepherd dog, the old philosopher of the mountain top whom all Hollywood knows and often consults.

“The whole world will be a-better for a-gazin’ on it,” mused Mandeville with a smile. “Strange old Peter.”

In echo I heard the words of Shelley spoken of his friend. “On whose countenance I have sometimes gazed till I fancied the whole world could be reformed by gazing too…”

It was a noble lament, for Shelley had just learned how that friend had deceived him. Perhaps the great poet saw more than was actually present in his friend’s face. But I’d rather think it was the friend’s failure to appreciate the power within himself which Shelley saw envisaged.

It is a tragedy common to pictures, the failure of a man to create his life in the image which the world holds of him.

Evangelizing Faces

If words can evangelize, why not faces? I left the shop thinking of idealized Faces worshiped by people in temples all over the world… Faces of Christ… of Mary… of Gautama the Buddha… of Krishna… Confucius… Mohammed… Lao-Tse… Faces of saints and sages and prophets who once were men.

I wondered impiously if they were actually adored as much as those other faces so miraculously filling the world of today; the faces of film gods and goddesses.

Men Made Gods

Familiarity rarely begets veneration. Rome is an irreligious city and a star is not without honor save in Hollywood.

We do not appreciate, nor do we fear, the influence of our idols as do people at a distance. We take them lightly. Yet a foreign critic of far perspective asks if we are not on the eve of a new religion with men made gods as in the days of imperial Rome.

The answer comes from still more distant Russia, where old gods have been thrown from the churches and in their places the images of men enshrined – Tolstoy, Turgenev and, among others, we’re told, Charlie Chaplin.

“Better the people should worship men of accomplished good than mere idols and fetishes,” so argues the government.

Even the church itself reaches down now and then to elevate a worshiper to a place with the worshiped.

All this I cite as evidence that the passion for sublimating a hero until he is made more than mortal is common to the human race.

The unconscious deification of picture idols is evinced in the very intolerance toward their human frailties. They are sentenced for deeds which a minister of the gospel might get away with. And this not thru malice but thru love of them.

The Art of Acting

When a screen star is dethroned for reasons of personal nature, the invariable cry goes up, “Why can’t a film artist be judged by his art alone?”

The answer is, because he is his art.

The sculptor works in clay, the writer in words, but the movie artist in terms of self. His is the most personal of all the crafts.

Pearl White once gave a classic definition to the art of screen acting. She said it was “the bunk.”

D. W. Griffith long ago declared that the camera penetrates to the soul. “Everyone can act except an actor,” said he, meaning that self-conscious histrionic gestures are not permissible on the screen where a player must be as real as the scenery in which he appears.

The art of screen acting at its best is the art of being. When we cease trying to judge it in the light of the stage and realize this fact, we will have comprehended much.

The variety of characters which a man can play depends upon the variety of his own nature, the conjuring power of his imagination and his physical appearance.

“I wonder sometimes when people congratulate me upon my performance in ‘Ben-Hur’ how much that performance would have mattered had I had a fat stomach,” muses Novarro ironically.

It would have mattered for less than nothing had he had a fat head. Still less had he possessed a small soul.

Ramón’s Infinite Variety

Novarro is a versatile actor. He was the witty, diabolical Rupert in “The Prisoner of Zenda,” the lyric pagan youth in “Where the Pavement Ends,” the dashing impertinent Scaramouche, the sly sardonic dragoman of “The Arab,” the princely and fine-souled Judah of “Ben-Hur.”

All these are distinct characters, yet each is Novarro. The difference in them is simply in the emphasis placed on his own characteristics. His art as an actor lies in his ability to project from his own nature those phases which the author has stressed in the fictional character.

Novarro exemplifies my definition of the art of screen acting — the translation of character in terms of self.

Because he is himself a complex and versatile nature, he can play many parts with fidelity, there are writers who can write with authority on many subjects and there are those, equally great, who specialize on one. A writer cannot compose beyond the zone of his own mind, no more can an actor create beyond the horizon of his heart.

Life’s Masterpieces

In arguing of the art of the screen we overlook the fact that the screen is a medium for something more than storytelling. It is a conveyance of the gods, a means by which exceptional personalities are presented to the world.

Certainly it is not the art of Greta Garbo that has cast an immediate spell upon the public, and it is not the high merit of the stuff in which she has appeared. It is — Greta Garbo, a singularly strange and interesting specimen of the human species.

And it is the mesmeric power of character, personality, soul or whatever you choose to term the Real of a human being, that has exalted such favorites as Mary Pickford, Norma Talmadge, Gloria Swanson, Pola Negri, Douglas Fairbanks, Emil Jannings, Harold Lloyd.

Wilde says, thru the painter in “Dorian Grey”: “I sometimes think there are only two eras of any importance in the world’s history. The first is the appearance of a new medium for art, and the second is the appearance of a new personality for art also…”

And further, as tho apropos of the screen: “Now and then a complex personality takes the place and assumes the office of art, is indeed in its way a real work of art, life having its elaborate masterpieces, just as poetry has, or sculpture or painting.”

In the screen we have the first exhibition place for these masterpieces. And with the discovery of this new medium for art came the discovery of new personalities for art also.

Will the Screen Yield a Leonardo?

The masterpieces of life to which Wilde alludes are also cited by the Italian historian, Vasari. “Occasionally,” says he, “Heaven bestows upon a single individual grace and ability, so that every action is so divine that he distances all other men and clearly displays how his genius is the gift of God and not an acquirement of human art.”

Such a man, says Vasari, was Leonardo da Vinci, “whose personal beauty and grace cannot be exaggerated, whose abilities were so extraordinary he could readily solve every difficulty that presented itself. His charming conversation won all hearts, we are told ; with his right hand he could twist a horseshoe as if it were made of lead, yet to the strength of a giant and the courage of a lion he added the gentleness of the dove.”

Thus Leonardo lives more vividly by the force of his own character than by his works as an artist, and he will continue to live in the love of man when those works have perished from their canvases.

It is not without the bounds of reason to suppose that the screen may one day yield such a personality. It already has produced unusual ones.

Why Stars Fall

Stars fall from popularity for two reasons: one is poor story material that obscures their personal worth in trash; the other is change in personal character. I have yet to observe one who fell because he had forgotten his “art” of pantomime.

“Praise is the most insidious of all methods of treachery known to the world,” says Balzac. “The policy of intriguing schemers knows how to stifle every kind of talent at its birth by heaping laurels on its cradle.”

Many is the starry cradle that has been heaped with laurel until it took the appearance and served the purpose of a coffin.

Hollywoods Amon-Ra

It was the custom of Alexander the Great to propitiate the gods of each country he conquered and so to bring the people into a willing subserviency. When, master of the world, he came as a ruler to Egypt, his first move was a visit to the temple of Amon-Ra containing an image of the god which could speak and move. Before Alexander had a chance to bow down before the god, the god approached and flattered him — “Alexander, thou art thyself a god!” So it was that the priests of Egypt conquered their conqueror.

Under the influence of Aristotle, his tutor, Alexander became a great and magnanimous ruler — master of all the world with the opportunity of becoming a veritable god. Under the influence of flatterers he was made to believe in his own godship before he had attained it, and at the age of thirty-three he died after a drinking debauch.

Hollywood has its Amon-Ra and Alexander repeats himself.

Doug the Evangelist

The exceptions prove the rule.

Douglas Fairbanks is one of them. Doug has been an evangelist of youth, spreading the gospel of never say die, dare to live dangerously, keep young your ideals of courage, hope and romance.

Doug once told me that he set out deliberately at the beginning of his career to preach the doctrines of youth, which are activity, clean living and the pursuit of ideals. He hasn’t done this by “educational” films. He has done it far more effectively by suggestion. Not a preacher, but an exemplar, he has backed up his screen ideal by his daily living. Thus he endures not by any esoteric gift for “acting” but by the greater gift of being.

Mary…

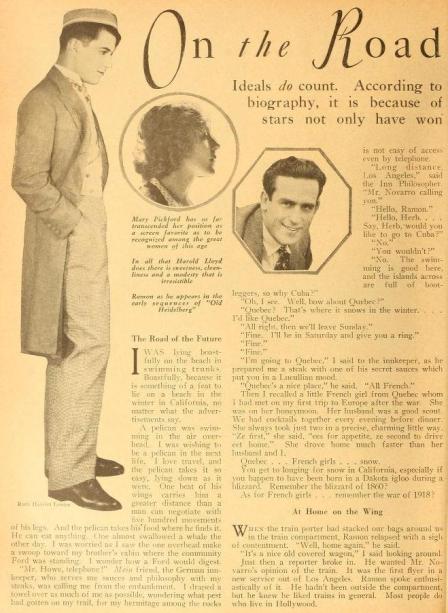

Mary Pickford has so far transcended her position as a screen favorite as to be recognized among the great women of this age. Perhaps that is the reason her screen children seem to have a lesser appeal. Her own womanly character overshadows them. She is greater than any specialized work she can do.

Norma, the Woman

Norma Talmadge goes wherever the Ladies Home Journal goes — and farther. This reception of her is not based on her art as a pantomimist but upon her typification of womanly ideal. She is in herself a very lovely portrait of Woman.

Harold, the Boy

Harold Lloyd exists for much the same reason as Doug. His screen characters are at one with his own. There is sweetness, cleanliness and a modesty that is irresistible. He is, in fact, the Kid Brother and Grandma’s Boy.

Novarro’s Future

Novarro has not stood the test of time as these great favorites have. He is just coining into his own. His rise has been rapid enough to dizzy an ordinary mortal. Tho an established favorite, he has appeared in only ten pictures: “The Lover’s Oath,” “The Prisoner of Zenda,” “Trifling Women,” “Where the Pavement Ends,” “Scaramouche,” “Thy Name is Woman,” “The Red Lily,” “The Arab.” “The Midshipman” and “Ben-Hur.” His next is “Lovers” from Echegaray’s great drama, “El Gran Galeoto.” This will be followed by “Old Heidelberg.”

Thus he is interesting mainly in terms of his potentialities.

Externally the omens are in his favor. He is with a successful organization. He is under the supervision of Irving Thalberg, whose particular gift is a shrewd insight to character values combined with the ability to match like elements in story, director and star. His belief in Novarro is manifest in a remarkable schedule of stories and directors.

«Young Hercules»

I visited the studio recently to see Novarro working under the direction of Ernst Lubitsch. It appeared to be visitors’ day on the set. Mary Pickford and Marion Davies had called, and in the sidelines was an old Indian gazing raptly at Novarro. He wore the make-up and the feathers of a chief. He was playing a part in one of Colonel Tim McCoy’s Western pictures on a neighboring stage.

“Hello there!” cried Ramón coming out of the scene and gripping the old chief’s hand. “How have you been?”

“Fine,” said the chief. “And you — you are as strong as ever, hunh?” He placed a hand on Ramón’s arm. «Yep, strong as ever. Some fighter you are!»

Ramón laughed and explained that the Indian had played extra with him in his first picture, “The Lover’s Oath,” a pictorial version of the “Rubaiyat.” In one scene Ramón was taken captive by two strong-armed Persians, one of them played by the Indian. The director told Ramón to struggle with them in a futile attempt to free himself. Ramón’s attempt was not futile. He hurled the Indian over the edge of the cliff on which they were working and all but hurled him into the Happy Hunting Ground.

“Some boy,” grunted the chief, who since that day has been a warm admirer of Novarro, never failing to visit him on the set when opportunity offers.

A worshiper to whom Ramón is “Young Hercules.”

Lubitsch’s Forecast

Lubitsch came over to speak to me and I left Ramón chatting with his Arapahoe friend.

“How does Novarro like the picture; he is happy, yes?” asked Lubitsch with solicitude.

“In seventh heaven,” I replied.

“Ya? So. I am glad,” replied the expansive little German. “I tell you the truth, that boy is giving a great — a marvelous performance If this picture is big with popularity, he should be the outstanding man on the screen. Ya, he should be…” He paced a few steps, then quickly turned. “This is not masquerade romance. No big gestures — so and so. That is acting. This is heart. He is just a simple boy who is a prince. A boy with a clean fine heart. I think that is like as Novarro, not?»

I agreed.

Ingram’s Faith in Ramón

Like every star who has responded quickly to a tine director, Novarro has been considered a director’s creation. This is a mistake. Neither Rex Ingram nor anyone else made a star of Novarro. He excited the enthusiasm of Ingram, who has a rare instinct for gift in an individual. Rex had an eliciting faith in Ramon and he worked with furious determination to justify it to the world. Novarro could not have started his career under a finer more discerning master. And he might well enjoy a glow of honest satisfaction —along with a lot of gratitude — upon the receipt of that telegram from Ingram, after the director had seen “Ben-Hur” in New York. It read simply: “You give a great performance, Ramón. I am very proud of you.”

«The Coming Great Tenor»

Novarro inspires a like faith in another of his masters, Louis Graveur, celebrated concert baritone, who has tutored him in voice. In an interview in Musical America, Mr. Graveur says: “In addition to possessing a tenore robusto voice of exceptional quality, Mr. Novarro is a thoro musician and an accomplished pianist. He is the coming great tenor.”

The Rôle of Ramón

Personally I believe that destiny has outlined an heroic role in life for Ramón Novarro and equipped him with all the gifts that are needed for playing of it. Whether its chief expression will be thru the medium of the screen or thru the medium of music, I do not know. It may be simply thru the art of living without the handicap of fame.

The best forecast of Novarro’s future lies in the faith which others have in him. It is his business to take the cue and see what they see in him, but always as an ideal which is just beyond.

He has the gifts. Everything depends upon his treatment of them.

In the way he lives, in the direction his mind takes, there lies the Road of Ramón.

May it lead — Ever Upward!

The End